The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Firmly Planted in South Dakota

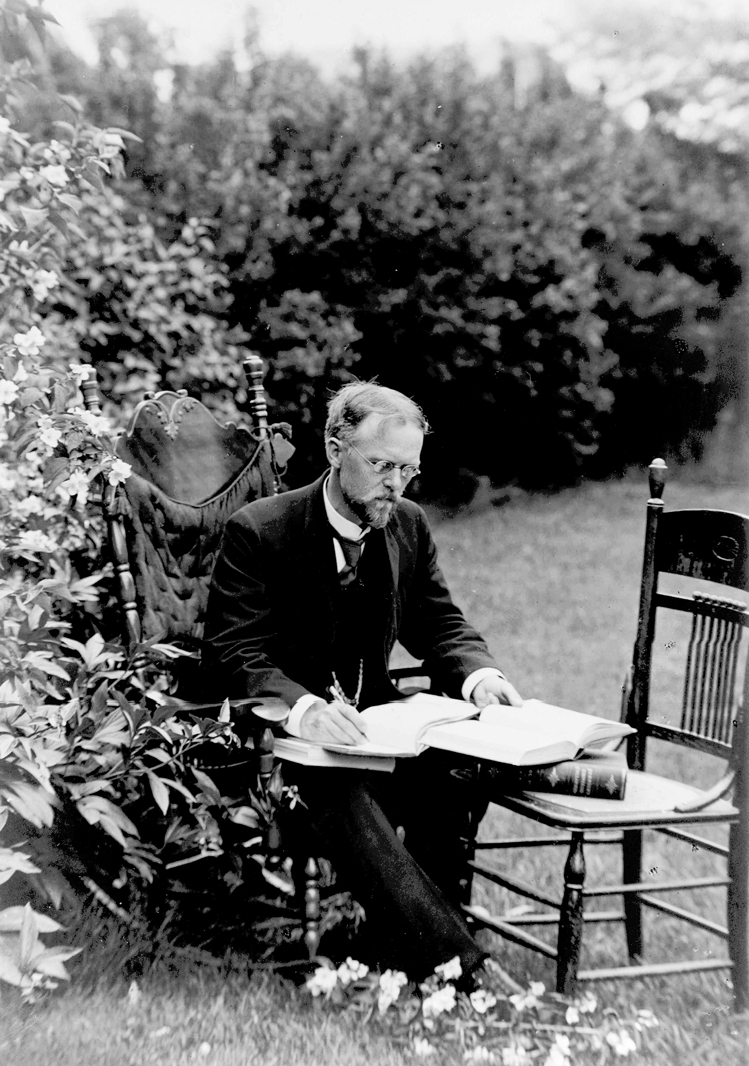

|

| Niels Hansen traveled to Russia, China and other distant nations in search of fruits, flowers and agricultural plants adaptable to the South Dakota climate and soil. |

For some South Dakotans, the name Niels Ebbesen Hansen is associated with alfalfa. Others recall that he introduced hardy fruits for their orchards. Some, noting his association with another plant breeder of renown, may remember him as “The Burbank of the Plains.” His contributions to the field of horticulture have been mentioned in magazines and newspapers for over 70 years. Writers delight in recounting his adventurous trips to the steppes of a Russia still ruled by the czar. Others refer to his forays into China, where bandits roved the countryside. To me he was grandpa.

These extraordinary adventures came at the turn of the 20th century, when Niels Hansen became the first plant explorer for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. His mission was to find plants that would grow in South Dakota and surrounding states. Plants brought from the eastern half of the country struggled to find sustenance in a semiarid land with cold winters. Hansen proposed the radical idea that South Dakota could grow virtually any plant if it were crossed with hardy strains of foreign plants. He spent his life as a horticulture professor at South Dakota State University proving that theory.

But there was more to the man than his adventures or his desire to introduce plants that would grow in what he fondly referred to as “my American Siberia.” A man of science, Niels was also a man of quiet Christian faith. He once told a group of students at a chapel meeting, “I felt I was doing the Lord’s work.”

Hansen was also a man of poetry. He once told a visitor that he arrived early to work so he could write a few lines of poetry each morning. “It helps get my thinking started,” he said. He often submitted poems to Pasque Petals, the magazine published by the state Poetry Society. His love of poetry endures in the stanzas of the SDSU song, “The Yellow and Blue,” which he wrote. Students saw him marching across campus with a tall, lanky music professor named Francis Haynes, beating out the rhythm of the song and lyrics. To some, they looked like Ichabod Crane and a shorter friend.

The fine arts were especially dear to Niels Hansen, and he supported them any way he could. Rain or shine, he walked his grandchildren to whatever cultural events were offered at the college. He introduced the Scandinavian tradition of the Maypole, a mainstay of the campus May Day celebration for many years.

An immigrant to America, Hansen was proud of his Danish roots and of the family that contributed so much to his character. He was named for a grandfather who had received the highest civilian award from the king for 50 years of service. Niels’ father served in the army and also received a medal from the king. His cousin was a member of the king’s cabinet during the German occupation. When he traveled abroad, Niels visited aunts, uncles and cousins.

Hansen attributed his love of art to his father, Andreas, a fresco painter and a loving, supportive figure in the son’s life. The fond letters they exchanged over the years showed how important that relationship was to both of them.

As important as foreign travels were to his professional life, his most important trip was taken in 1897 — important not because of the prized alfalfa he discovered, but because it was on this trip that he wrote a letter proposing marriage to the woman he had been courting for six years.

The romance began when he was an assistant professor of horticulture at Iowa Agricultural College, now Iowa State University. While at Ames, Hansen spotted a teenager, Emma Pammel, who had come to attend the college and to live with her brother Louis, head of the botany department. Rules about dating students were strictly enforced, but even if they had been more lenient, Emma wanted nothing to do with the son of an immigrant painter. The family still has Niels’ invitation to Emma to attend a college event. She returned the invitation with the written comment, “No! No! No!”

|

| Hansen built South Dakota State University's horticulture department, but he also dabbled in poetry and writing. He composed the lyrics to "The Yellow and Blue," one of SDSU's school songs. |

Niels’ courtship efforts were aided by his friend George Washington Carver, a student at Ames who later gained national renown for his teaching and his work with peanuts and other plants at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Louis Pammel had befriended this ambitious son of a former slave, admiring his desire for education.

Being black, Carver was not allowed to live in a dormitory, so Pammel arranged for him to live in the basement of the botany building. As their friendship flourished, Carver spent many evenings with the Pammel family. Also a classmate of Emma, he had access to the family that Hansen could only hope for. Seeing Hansen despondent over the lack of progress in his pursuit of Emma, Carver would ask with a broad smile, “Would you like me to take some roses from the greenhouse to Miss Pammel tonight?”

After he left Ames to become the professor of forestry and horticulture at the college in Brookings, Hansen persisted in this courtship. “Of course I think more of you than of ‘a mere friend’ — a thousand times more,” he wrote to Emma. “How can I help it? You have known that my sentiments are more than friendly for a long time. I know I tried very hard for a long time to forget you but could not make the slightest progress in so doing.”

“When he sees something of value he knows it, and when he goes after a thing, he gets it,” Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson once said about Hansen. Such was his pursuit of Emma, whom he adoringly called “My White Lily.”

After six years and many letters, Emma, who had been pursuing a career in teaching, finally succumbed to Niels’ entreaties. They were married in the fall of 1898. They were considered a handsome couple, she a fashionable, vivacious wife who entered into faculty life with gusto, he proudly escorting her to faculty balls, where they became known for their elegant dancing.

Six years later their idyllic marriage ended. Emma was stricken with appendicitis when she was six months pregnant with their third child. In those days there was no local doctor who would operate on a woman in this condition, so Hansen frantically wired to Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. A doctor agreed to come, but was held up in a blizzard, and arrived too late. Emma’s appendix burst, and peritonitis set in. She lingered five days before dying in mid-December, 1904.

Heartsick with grief, Hansen now found himself unable to care for the two small children, Eva, 5, and Carl, not quite 2. The Pammel grandparents took the children into their home in La Crosse, Wisconsin. Hansen was now without wife or children. This sorry state existed for three years, until he married Emma’s sister, Dora, who had been helping to care for the children.

After Emma’s death, Hansen made two more trips to Siberia for the Department of Agriculture, the last in 1908. Then he and the department parted company. He had overspent his budget, and department staff persuaded Secretary Wilson to drop Hansen from the roster of plant explorers.

Hansen may not have been surprised. His relationships within the bureaucracy had been difficult from the start. He had been hired by and reported directly to Wilson, a friend from his Iowa days. Some staff members resented his position as a favored employee. The situation was likely exacerbated when the secretary praised him publicly: “I have 1,200 men under me, but none who knows how to work like Hansen. There is only one Hansen.”

Hansen may have failed in Washington politics, but he could be persuasive with the South Dakota Legislature. He stood before the farmers of the legislature and pleaded his case for more research funds. Three times they granted him money for different projects. They provided funds for the first commercial-size greenhouse on state property. They sent him to Siberia for more alfalfa, and they were persuaded to fund a trip to China to find hardy pears. “You can always appeal to a man’s stomach,” Hansen joked.

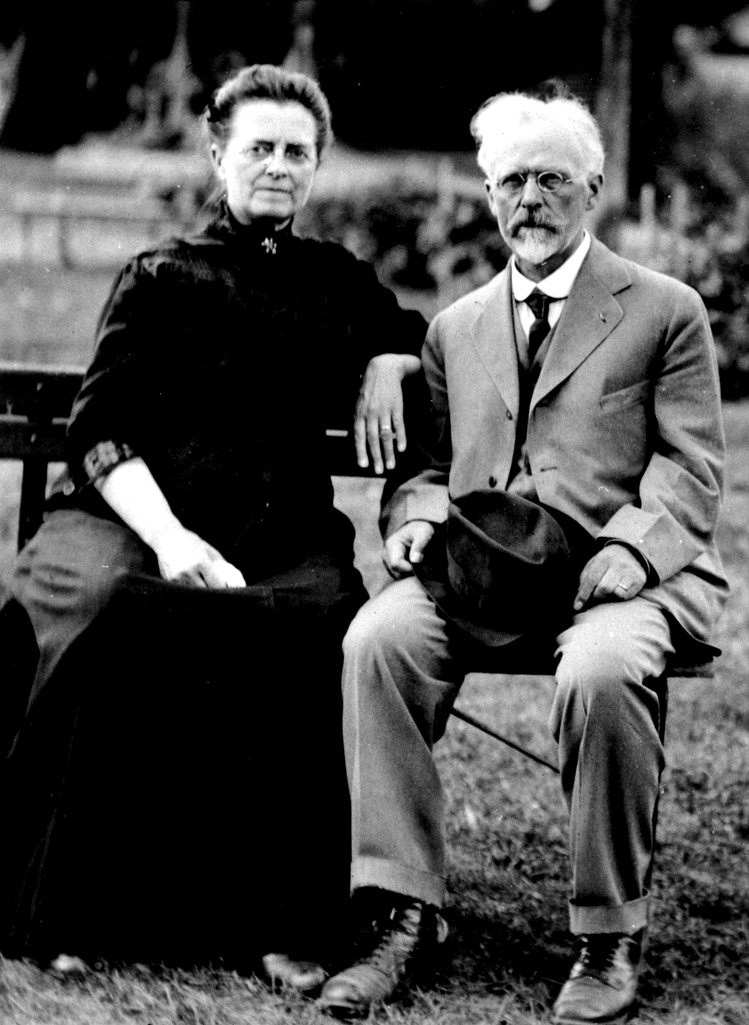

|

| Hansen, pictured with his wife Dora, remained active until shortly before his death in 1950. |

The State Fair at Huron was also important to Hansen. He would fill the Horticulture Hall with flowers, fruits and agricultural products from the experimental farms and orchards across the state, an opportunity to show farmers the variety of plants they could grow in South Dakota. One year he displayed over 500 kinds of gladioli. He always enjoyed talking to farmers about their problems.

Reporters delighted in interviewing Hansen, because he had a delightful self-deprecating manner. They could count on some witticism or quote. Interviewed in retirement, he told one reporter that he had to keep working to prevent “ossification of the coco.”

One year at the State Fair he showed his impish sense of humor when he set up a small pond in the center of the Horticultural Hall, purporting to contain “invisible fish.” Many an onlooker peered into the pool trying to spot them. Those who knew Hansen were not surprised at this harmless bit of tomfoolery.

He once remarked, “I can recommend overland travel by troika as a sure anti-fat cure. But I can also say that after a 700-mile ride I have never cared about sleigh riding.” Another time he humorously commented, “Riding hundreds of miles in a springless wagon is good for indigestion, if you can stay in the wagon. It settles your food.”

A visitor once suggested, “I suppose you could even breed a square pea that would stay on your knife!”

“As a matter of fact, I found a three-cornered pea once in Asia that might turn the trick,” Hansen shot back. “Some day I may get to work on that.” Praised for a new red-fleshed apple, Hansen remarked, “It’s like a candied apple without the cinnamon. We may be able to breed that into it later.”

After Hansen’s death, the Brookings Register observed in an editorial: “Those who have commented upon his traits of character and temperament have all missed one thing, and that was his sense of humor. He could illuminate his tale with sly and subtle humor which made his discussion of even highly technical matters interesting to the untrained.”

It was on the many foreign trips that Hansen proved his courage. Once, far from civilization on the steppes of Russia, a peasant guide tried to rob him. Hansen quickly showed the guide the special permit he carried with the seal of the czar attached. The guide recognized the seal and realized Hansen was under the protection of the emperor. He crossed himself, knelt in submission, and promised to fulfill his duties.

Another trip took him through a region of northern China where bandits roamed. He later told his family the grisly story of how the road into one village was lined with the heads of bandits impaled on spikes as a warning to would-be marauders. “But I kept on with the pear work,” he commented casually.

Hansen gave lectures on anything from Russian agriculture to the propagation of roses. Sometimes he strayed from his major field and rendered opinions on topics such as “The Sublimation of the Libido,” or the atom bomb. He could easily fill a hall because his speeches, given in a soft voice that retained a slight Danish accent, were amusing and insightful. But those who heard him speak might have been surprised to learn that he had overcome a speech impediment with elocution lessons and diligent practice.

Hansen enjoyed the movies, and rarely missed the offerings of the theaters in downtown Brookings, the Fad and The State. He had a preferred seat in the theaters, which the ushers faithfully set aside for him, sometimes asking people to move if they sat in “Professor Hansen’s seat.” He regularly took his grandchildren to Sunday matinees, then to Fenn’s ice cream store.

Those who sat behind Professor Hansen witnessed his passionate involvement with a movie. In one, the hero was alone in a desert without water, struggling through the sand, obviously dying from thirst. Hansen kept muttering, “Cut the cactus! Cut the cactus!” Not surprisingly, the hero finally found the cactus that contained water and saved his life.

Hansen remained active until a year before he died. In his 84th year, he began to fail. The once sturdy body that had taken him across the windswept steppes of Russia and on many treks across the prairies, now was slowed by inflammation of the heart. In his last few weeks of life, he could recognize only his son Carl. His thoughts wandered back in time. Once he became extremely agitated, shouting, “Where are the keys to the apples? Where are the keys to the apples?”

Carl knew exactly what concerned his father. He was referring to his keys — the research notes on the many cross-pollinations he had made. When Carl reassured him they were safe, his father became calm.

Finally, in 1950, Niels Hansen’s infirmities required hospital care. One evening his grandson, David Gilkerson, and his wife came to visit. They found him curled up asleep on the hospital bed. On the bedside table, a stranger had left a tribute to Hansen’s life — a single pear. It was as though the visitor had said, “See, Professor Hansen. This is what I grew on one of your trees. Thanks for all you have done.”

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the July/August 2004 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments