The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Hot Water and Old Bones

Apr 12, 2017

|

Last summer our family spent an afternoon at Evans Plunge in Hot Springs. Its warm-water pools have attracted people for decades, but it was the first time we had ever been there. I wasn’t prepared for the rocky bottom in the main pool, but the kids enjoyed the water slides, games and watching other swimmers try to cross the width of the pool Tarzan-style by swinging from ring to ring (neither of them were tall enough to try on their own).

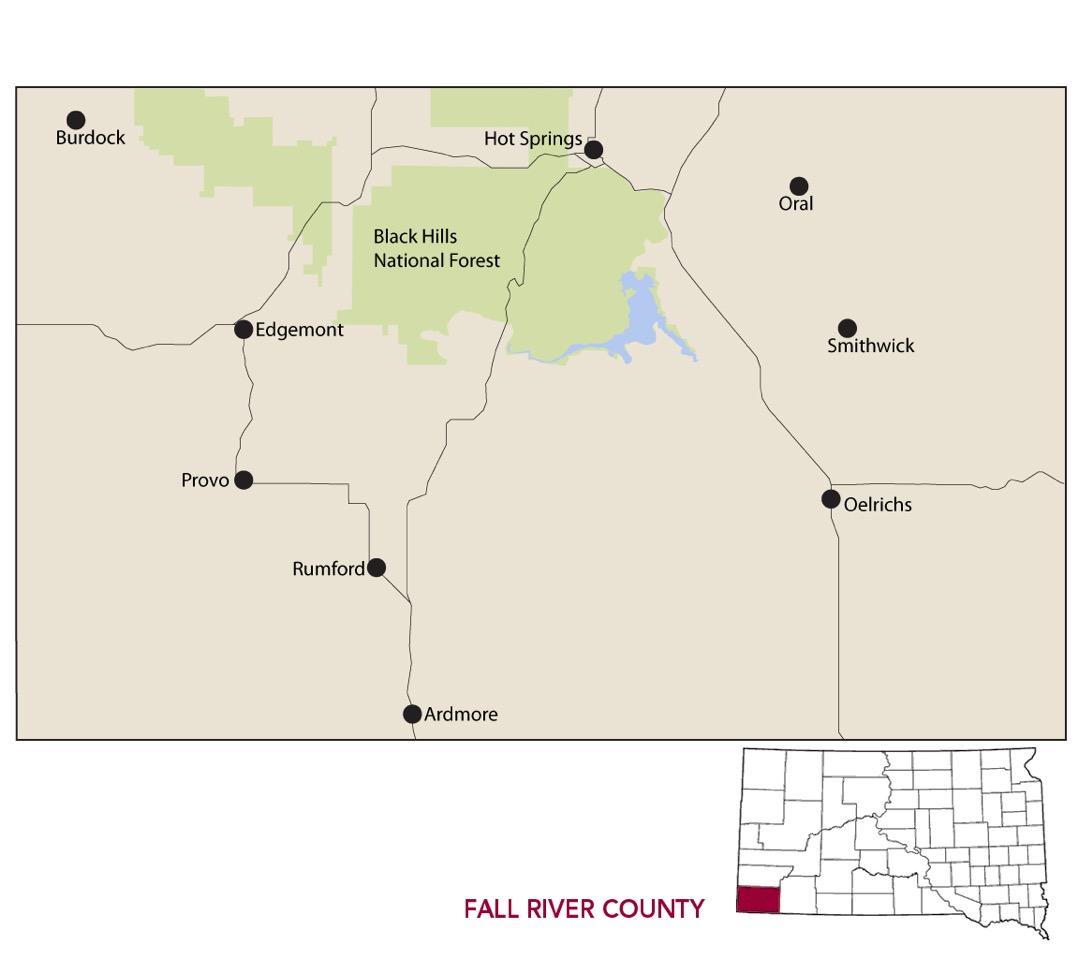

Hot Springs is the seat of Fall River County, which encompasses 1,749 square miles in the far southwestern corner of South Dakota. As is the case with much of arid West River, rain is tough to come by. The county averages 20 inches or less of rain a year, which is why it seems so remarkable that water played such a tremendous impact on life in that part of the state.

We can say it began 26,000 years ago, when an enormous sinkhole formed on what would eventually become the southern edge of Hot Springs. The prehistoric creatures that roamed the continent — mammoths, giant short-faced bears, camels — ventured to the oasis to drink, only to discover its banks were too slippery to ascend. They died and were buried there, lost for millennia.

|

| Visitors file past mammoth bones that lay buried for thousands of years. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism. |

Then in 1974, Philip and Elenora Anderson began to develop that land for a housing project. Dirt work stopped immediately when a bulldozer unearthed a huge tusk. The Andersons donated the land to a nonprofit organization that built an enclosure over the site. Dr. Larry Agenbroad of Chadron State University in Nebraska oversaw the initial paleontological work there and stayed until his death in 2014. Today, visitors can stroll through the 23,000-square-foot Mammoth Site on walkways that provide views of volunteers working to expose fossils. The most recent count says that scientists and volunteers have discovered 61 mammoths, plus fossils from other land and sea creatures.

Fred Evans capitalized on water when he arrived in the Black Hills in about 1875 and heard about Minnekahta, or the warm water springs where Native Americans sought healing. The springs that eventually became Evans Plunge had a relatively inauspicious beginning. One early settler who owned the land on which the main spring is found reportedly sold it for a horse valued at $35. Evans built a grand sandstone hotel and enclosed the spring in 1890. He advertised its mineral waters, flowing from the earth at a steady 87 degrees, as a cure-all.

|

| Hot Springs' Freedom Trail follows the Fall River through town. |

People came from throughout the country to test the springs’ medicinal qualities. The wife of a Nebraska senator visited and returned home feeling like a new woman. “Mrs. Paddock has fully recovered after many years of suffering, a result wholly due to the mineral properties of the Hot Springs water,” reported the Hot Springs Star. I don’t recall feeling particularly rejuvenated after our visit last summer, but the fun we had surely did something for our spirits.

If water could make a Fall River County town, it could also break it. A few years ago, a freelance photographer submitted a batch of photos he’d taken on a trip through Ardmore in the far southern reaches of the county. He thought at the time that maybe a couple of people still lived there, but it seems to be considered a ghost town today. Old cars, buildings and even the town’s water tower still stand, but there’s no life to be seen. Ardmore sprang up as a railroad town in 1889, but water was scarce. Hat Creek proved an unreliable source. A train car brought the last load of water into town more than 40 years ago. Still, Ardmore holds a special place for the people who grew up there. They still comment on the photo gallery we created from that batch of photos, almost four years after we originally posted it.

|

| Old cars and a water tower are among the remains of Ardmore. Photo by Joel Schwader. |

Fall River County is also the source of some historical oddities. The community of Igloo was created in the early 1940s when the U.S. Department of Defense located the Black Hills Ordnance Depot in rural Fall River County. Hundreds of dome-shaped structures resembling igloos began to rise across the prairie. Thousands of people lived at Igloo until the government cut the depot’s funding in 1967. Look closely when you pass on Highway 471; the strange ruins are still visible.

The canyons around Edgemont are home to mysterious petroglyphs that are thousands of years old. Several years ago, I talked to John Koller, who grew up on a 2.500-acre ranch along the Cheyenne River east of Edgemont. “I was told they were there, but as a kid out here, you work,” he said. “So when you pick up a rock and throw it at a cow to get it out of a box canyon, you don’t have time to stop and look at these wonderful finds. I crawled around these petroglyphs all the time, but didn’t pay attention.”

Later in life he began to appreciate the ancient art that surrounded him. He estimated one drawing to be at least 8,000 years old, while others were between 2,500 and 3,000 years old.

|

| Hundreds of dome-shaped structures were constructed when the Black Hills Ordnance Depot located in rural Fall River County in the 1940s. |

Perhaps the most interesting oddity I discovered while poking around Fall River County is a map that Hot Springs businessman Orlando Ferguson used to support his theory that the earth was square and stationary. Ferguson had the map printed in 1893. It resembles a bundt cake pan turned upside down. The continents and oceans lie around an indented ring, while the North Pole is raised in the center. The sun and moon are attached to an actual pole rising from that point.

His astronomical principles were based on a very literal interpretation of the Bible, beginning with the reference to angels visiting the four corners of the earth. From there, he developed his square and stationary idea. He claimed the sun was 30 miles in diameter and just 3,000 miles from earth. His reasoning? If you stand at the equator on March 21, when the sun is directly overhead, then the distance you can walk north or south without casting a shadow is equal to the diameter of the sun.

He also shunned the idea of gravity. Instead he thought atmospheric pressure held people down and pushed the oceans up the sides of his indented map. Stop by the Pioneer Museum and take a look at the map and a pamphlet he had printed. Chances are you won’t buy what Ferguson was selling, but there are plenty of other natural and historical wonders to be found in Fall River County.

Editor’s Note: This is the 34th installment in an ongoing series featuring South Dakota’s 66 counties. Click here for previous articles.

Comments